Cultural identity through an Indigenous vision — inspiration for UHU artistic creation by Andrea Gonzalez and Stéphane Nepton

The article is presented in partnership with the Conseil des arts de Montréal

As an extension of their carte blanche at the 41s edition of the Festival, copresented with Présence autochtone, Conseil des arts de Montréal and Wapikoni mobile, Stéphane Nepton and Andrea Gonzalez today share an article offering a reflection on how Indigenous cultural identity influences artistic creation, offering innovative perspectives on intergenerational transmission and the use of digital arts to redefine notions of tradition and contemporaneity.

Stéphane Nepton and Andrea Gonzalez are behind the Uhu Indigenous Project, which promotes school retention, the transmission of Indigenous knowledge and cultural health through intergenerational digital arts workshops.

Naomi Fontaine (Innu): “Our culture is our compass, it guides us through life and reminds us of who we are.”

From an Indigenous perspective, cultural identity is a fundamental source of inspiration for artistic creation. It is based on language, that essential tool that weaves links between individuals, creating a social and collective fabric that is reflected in each and every one of us. This stems from our shared experiences, those moments that evolve over time and help shape our identity. At the heart of this reflection, crucial questions emerge. How can we make room for the discovery of new facets of ourselves that can enrich our artistic creations? How can we transcend our pre-existing identity, the one that has at some point defined us? And how do we deal with the identities that have been imposed on us?Cultural identity is not an innate given, but rather the result of personal introspection and the way others perceive us, making it a fascinating and sometimes disconcerting construction process. It’s an intrepid journey, by turns captivating and dizzying, a quest marked by discovery, healing, forgiveness and rebirth. Ultimately, what does cultural identity mean in relation to art and intergenerational transmission?

Art, as a creative expression emanating from both the individual and the collective, plays a crucial role in this context of cultural identity. When we talk about the formation of bonds through language, and how our shared experiences evolve over time, art presents itself as a powerful means of communicating, interpreting and reflecting on these experiences. Artists, whether using painting, music, dance, literature, film, digital or other forms of expression, create works that reflect, shape and influence collective identity. Creation is a powerful manifestation of cultural identity. It is both a reflection of our collective experiences and a medium for questioning them. It thus helps shape our understanding of who we are, as individuals and as a society.

Artistic creation offers a precious space for exploring new facets of our being, encouraging experimentation, creativity and reflection. Artists are often tasked with challenging pre-established norms, deconstructing imposed identities and proposing new perspectives. As a result, art invites us to rethink our own identity, to redefine it through an artistic prism. Resistance is created in the face of imposed identities. Artists can choose to create works that challenge stereotypes, prejudices, the consequences of colonialism or cultural oppression, creating a space for liberation and emancipation. Artistic movements such as surrealism, feminism and contemporary art have often been vectors for the affirmation of new identities, rejecting those traditionally ascribed to them.

Art plays a central role in the intergenerational transmission of cultural identity, and this is no different in indigenous communities. It acts as a powerful vehicle for transmitting a culture’s values, traditions and stories from one generation to the next. It is often a privileged means of preserving cultural traditions.Art offers Indigenous artists a means of reconnecting with their cultural heritage, but also of developing new forms of expression that are adapted to them. Today’s generation has mastered the digital medium, a channel they have made their own and with which they are comfortable exchanging. This allows them to create and communicate in a way that is unique to them. But how can this technology be used to promote and transmit their traditional cultures? Can digital technology become a vehicle for the evolution of native arts, alongside more traditional art? Could yesterday’s mediums be metamorphosed over time by new technologies? For example, would a digital drawing generated by artificial intelligence and inspired by works of the past constitute a new form of so-called traditional artistic expression? At what point does traditional art shift from contemporary to heritage? Will digital art be included in this definition?

Through its “organic/digital” workshops, the Uhu collective offers a contemporary exploration of indigenous cultural identities using new digital media. We offer an intimate experience linking cultural identity, knowledge transmission, community and territory.

Wawiesinahikan workshop [why-é-sann-nikann]- circle, round, circular form in Atikamekw.

Uhu participates in Camp Matakan, located on one of the islands of immense Lake Kempt, a forty-minute boat ride from Manawan. Every year, this site welcomes young people from the Atikamekw community. They are invited to spend several weeks on the site with the elders, in order to arouse their curiosity about their culture through contact with the knowledge keepers. The result is a unique encounter that fosters intergenerational transmission, blending tradition, knowledge and culture.

One example of the workshops we’ve designed and run here is the creation of digital Atikamekw mandalas. Derived from Sanskrit, the mandala represents a symbolic circle linking interiority and exteriority. Indigenous peoples in North and South America have used the mandala in a variety of ways: to represent a deity or the universe, to symbolize a spiritual path, a state of mind, or even to ward off evil spirits, as in the circular motif of the dream catcher1.

The circle has great importance in native culture as a symbol of a circular path to healing, a method of self-care. The mandala is also recognized as a therapeutic tool, its creation and analysis helping to reduce stress and anxiety by offering a personal exploration through shapes and colors.

It’s a workshop in which traditional mandalas are revisited in a digital format. By giving form to these symbols, created, imagined and crafted by the Atikamekw people using today’s technologies, the Uhu collective explores in an avant-garde way the encounter between cultural identity, tangible and intangible heritage, while forging a respectful dialogue between tradition and artistic innovation.

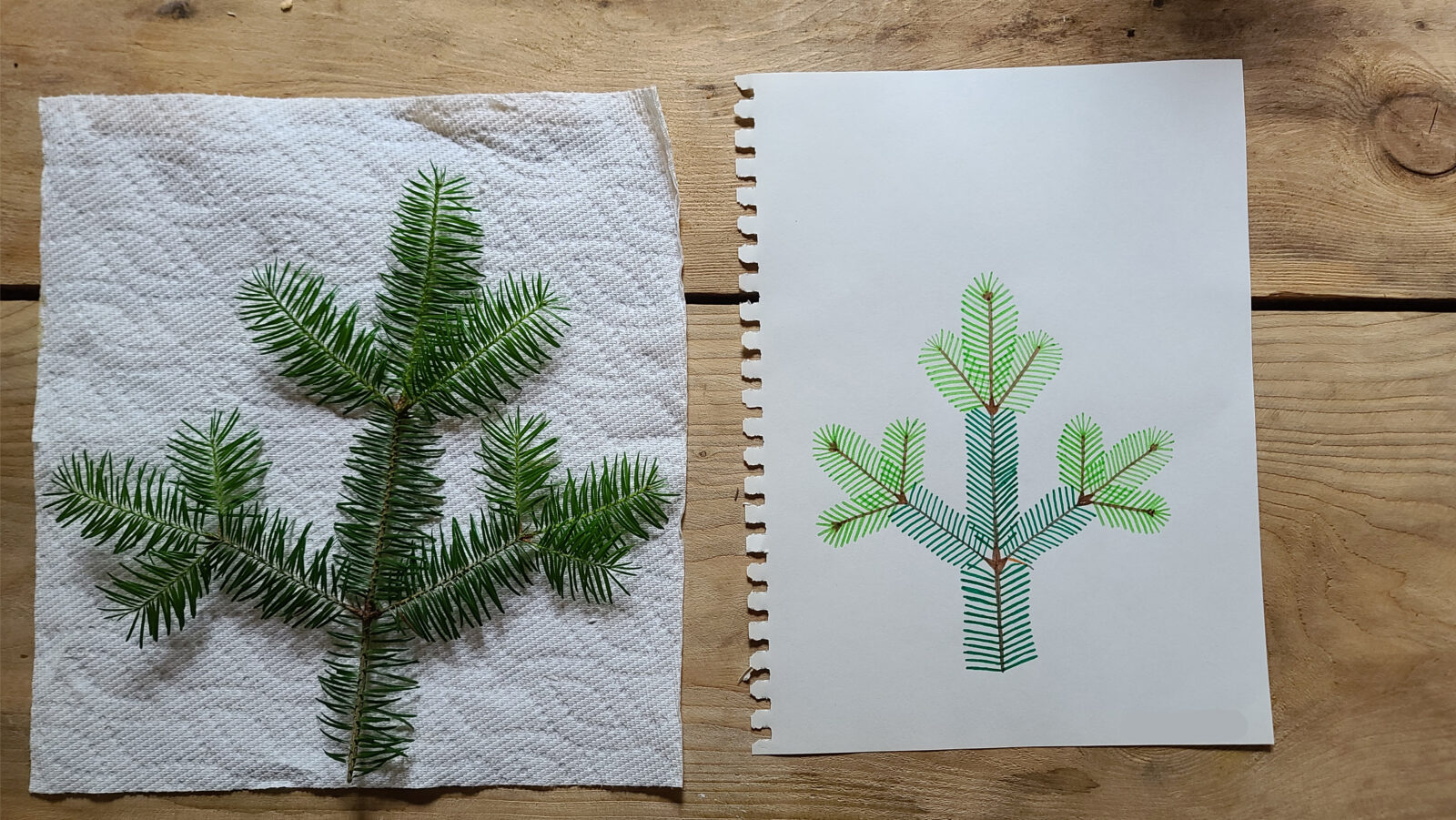

The first stage of this creative process, based on the traditional symbol of the mandala, consists of an immersion in the heart of the Atikamekw forest in the form of a walk and observation. Participants were invited to gather various natural elements such as bark, stones, leaves, mushrooms or flowers, according to their intuition at the time. The purpose of this gathering was to reconnect participants with their ancestral territory in a sensory, embodied way. Involving touch, sight and smell, this immersion in the natural environment encourages a state of full awareness and creativity. Back at camp, all participants laid their harvest on the table, sharing their pride and amazement at some of their finds. Many shared anecdotes and information about their exploration of the land. It was a moment that encouraged sharing, knowledge transfer and listening.

The second phase of the workshop was to take the elements gathered and reproduce them, in their own way, in the form of illustrations, using a variety of media. The pencil strokes and choice of mediums allow complex, deep-seated emotions to be expressed unconsciously, offering an alternative means of communication that is above all intuitive and playful.

In the final stage, participants had the pleasure of seeing their cartoons animated and displayed in a completely new art form. By taking a photo of the illustrations and transferring it into animation software, we converted the illustration into the creation of a digital kaleidoscope. We had access to an array of options that allowed us to modify the digital mandala as we wished. We highlighted these works, which symbolize the Atikamekw territorial connection, by projecting the mandalas onto a building in the camp. An identity enhancement under the stars that really made sense to the participants.

In light of this experience, we believe this new art form is becoming a powerful form of inspiration in all its forms. As First Peoples have not had the opportunity as individuals and as a society to build themselves without the ravages of colonial history, this artistic expression has enabled and enables them to name and claim culture and identity, while deconstructing the fixed and romantic stereotypes long perpetuated by colonizers.

Cultural identity is an evolving dynamic between past, present and future. This movement between three times gives meaning to our being and defines our perception of the world. We are no longer what we used to be, but not yet what we want to become. There is a diversity of identities, each one plural, heterogeneous and mixed. Even if many individuals identify themselves in different ways, they all agree to come together under a common culture, regardless of their personal or community path to cultural reappropriation and identity.What prevents historical amnesia, and the profound effects it can have on an individual’s life, is being able to experience a work of art, or take part in its creation, which provides fertile ground for the search for cultural identity reconnection. In other words, works that help to reconnect with one’s culture and remember history are important for personal development and for the transmission of cultural identity to future generations.

Art in all its forms will serve to understand worldviews and ways of thinking, and may even influence identities. This is why intergenerational transmission is an asset in identity-building. It is a powerful way of strengthening the bond between generations. Community elders can share their knowledge and artistic expertise with younger members of the community, thus fostering the transmission of culture-specific skills and knowledge.

One point of convergence between identity through us and the intergenerational transmission of knowledge lies in the crucial importance of history, both personal and collective. Cultural identity is formed through life experiences, interactions with the environment and an understanding of our own history. Similarly, the transmission of knowledge involves the telling of stories, the sharing of experiences and the communication of narratives that enable future generations to better understand their origin and essence. History and art, as well as intergenerational transmission, are fundamental pillars in the construction and preservation of cultural identity. History is the foundation of every society, on which its culture, and therefore its identity, rests. As the activist Marcus Garvey so aptly put it, “A people who do not know their past, their origins and their culture are like a rootless tree.“

In the end, identity is a continuous journey, where we skim the surface, explore in depth and glimpse with tenderness, while remaining aware that its essence remains enigmatic. It changes with the seasons of life, never the same, but true to itself. Elusive, she remains a human mystery constantly in search of understanding.

Andrea Gonzalez and Stéphane Nepton have been developing concepts for the transmission of indigenous knowledge through intergenerational digital arts workshops for several years now. Their artistic journey is characterized by a reaffirmation and rediscovery of their origins, which enriches their artistic approach.

“We share some very strong points in common. We’re both uprooted and rooted, half-Chilean, half-Italian and members of the First Nations. We’re also both in search of our respective identities, which are constantly evolving.”

We emphasize here that the ideas and reflections presented in this article reflect the author’s artistic vision and thoughts. The English translation has been automated via DeepL, and it is important to note that certain nuances or original intentions may have been altered.

1. Mark, J. J. (2020, octobre 13). Mandala [Mandala]. (C. Martin, Traducteur). World History Encyclopedia. Excerpt from https://www.worldhistory.org/t…