Trailer

Trailer

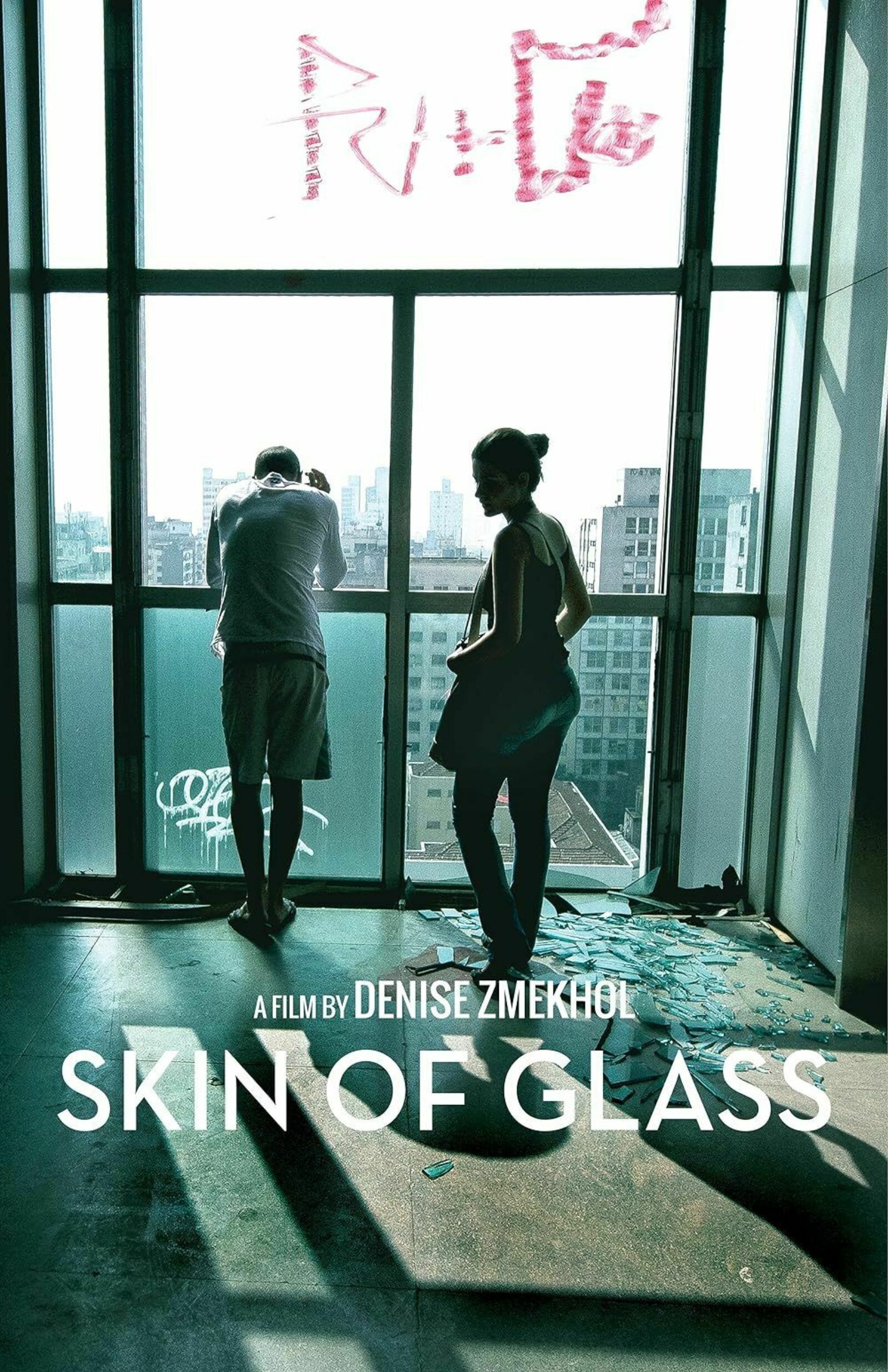

Best Feature Documentary at the Barcelona International Architecture Film Festival, finalist at the Venice Architecture Film Festival and winner of an Audience Award, Skin of Glass is a poignant exploration led by Arab-Brazilian filmmaker Denise Zmekhol. The film delves into her emotional journey upon discovering that her father’s iconic architectural creation became a refuge for hundreds of homeless families in São Paulo. Amidst tragedy — when the Pele de Vidro collapses during filming — Zmekhol intimately engages with the building’s inhabitants, unraveling a tale of resilience amidst architectural grandeur. Seamlessly blending personal and political narratives, the film reflects Brazil’s turbulent evolution. It adeptly contextualizes historical economic decline while shedding light on present-day social movements. Technically brilliant, the film enchants with its intimate storytelling, captivating visuals and emotive soundtrack.

In presence of the director Denise Zmekhol on March 23, 2024 at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montréal

Word of direction

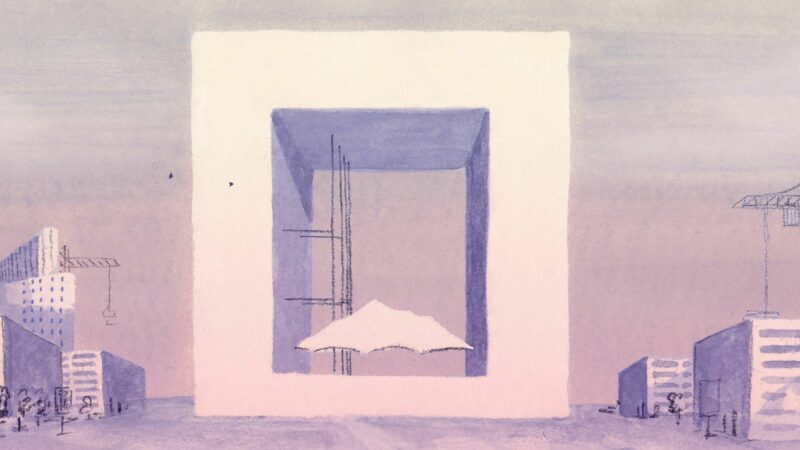

In 2017, after two decades as an immigrant in California, I hear of a controversy in Brazil about Pele de Vidro: internationally renowned among architects, it has become occupied by some hundreds homeless people after being left empty for several years. The news reopens long-shut doors to a father I lost too early. Determined to somehow reconnect with him personally and as an artist, I return to Brazil seeking traces of him in the gleaming glass-walled office tower in the heart of São Paulo — the first of its kind in the city.

Looking up from the sidewalk, I encounter the building for the first time since my childhood. Four decades after my father’s death, I’m stunned to see it riddled with graffiti and filled with broken windows through which drying laundry and curtains billow while residents lean out to survey the city below. As the shocking state of the building begins to sink in, my curiosity grows and I set out to meet with those who have made my father’s masterpiece their home. Individuals functioning as informal landlords who charge the residents fees and claim to be maintaining the building turn me away. Frustrated but realizing how little I know, I meet Pericles, a passionate housing activist. He helps me understand São Paulo’s housing crisis and the goals of local activists, showing me some of the other 70 abandoned buildings now occupied by homeless people throughout downtown São Paulo. I discover that each occupied building is unique and organized differently. Pericles is unable to negotiate my entrance in Pele de Vidro, which makes him suspicious, since the people handling maintenance of other occupied buildings are activists and welcome me with open arms.

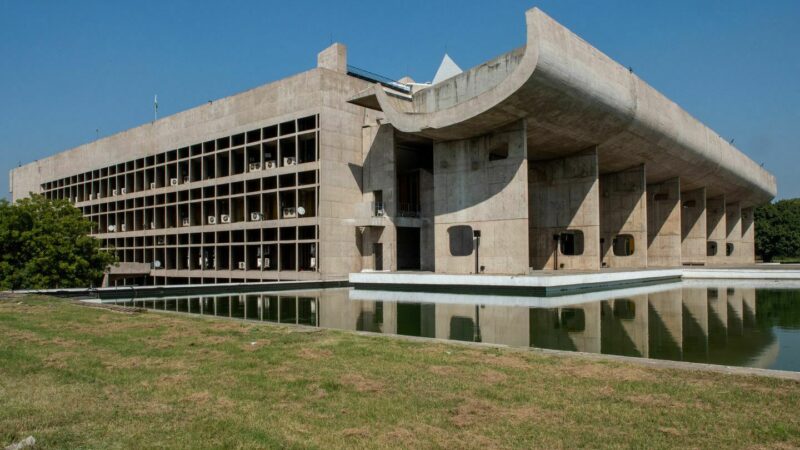

Being denied entry evokes the frustration and longing of my exile from my father’s life and work. Our estrangement began the year before he died, when he left our family. While repeatedly trying to negotiate my way inside the building over an extended period, I seek out people who complicate my childlike view of my father and his place in Brazil’s cultural history: architects and journalists who knew him and bring Brazil’s golden age, the early 1960s, alive. I learn from my father’s colleagues how architecture was stunted during the dictatorship that followed, and, more personally troubling, that my father did not actively resist the coup. Some of his friends did, and suffered the consequences of arrest, interrogation and exile.

These conversations raise questions of belonging and exclusion, the multiple meanings of shelter, displacement, access, and our own relationships to the buildings that surround us. I start to realize how different from my own worldview and political perspectives my father’s beliefs probably were. If he had lived, would we have drifted even further apart? Having grown up in a house he designed, how am I to think about this building of his that is now a home for others? I find myself drawn to these people who, like my younger self, call one of my father’s creations home.

After months of negotiations, the Pele de Vidro occupation leaders deny my request to film in the building. But I’m granted a glimpse inside in another way; a filmmaker who had documented the occupation’s early days sends me footage which allows me to vicariously experience the daily lives of residents inside the building. I reflect on my father’s experience as an immigrant, a Syrian refugee whose 280 project drawings played a significant role in Brazilian architecture, and his building’s latest residents, many of them immigrants from as near as Peru and as far as the Congo, who have not been welcomed by their new country as my father and I were.

Five months later, now back at my apartment in California, my cell phone buzzes insistently. It is May 1, 2018, and the Pele de Vidro is on fire. Phone calls and texts proliferate as I search for news. Footage on my cell phone captures the building engulfed in flames, and I watch its sudden collapse in an explosion of ash and debris. I am overwhelmed with emotions. How many have died? How can I accept that the building my father designed to celebrate the future has come to this tragic end in a city so dystopian that it would have been unimaginable to him? I get the next possible ticket to Brazil, asking myself during that long flight what might remain.

When I arrive, police cars, ambulances and the press are surrounding the street in front of the building. Orange firefighter helmets emerge from the smoke as rescuers search for survivors. Dust rises from the debris that was the Pele de Vidro. At least seven people are buried in the ruins, and several are missing. Hundreds have lost a home. I am devastated. The whole city is mourning the human tragedy and the destruction of a cultural landmark. For me, there is another, very personal layer of grief: I feel as though I have lost my father all over again.

Blindly, I turn the corner and discover people setting up tents, moving as if in slow motion – or in shock. The displaced residents are creating an encampment outside the building and now, without the occupation leaders there, I can freely approach them. I spend the next month getting to know dozens of individuals and families, including several I’d seen from their windows. They tell me they were never consulted about speaking with me and would have enjoyed showing me around the building. They add that the people who had kept me out fled the fire and locked the residents in. Police have issued arrest warrants for the coordinators, believing them responsible for the fire. I show the residents my footage from outside the building and they enjoy seeing themselves in their former home, intact again.

My relationship with them deepens over time as I start to not only see the building and Brazil itself from their perspective, but also consider how the world’s cities accommodate their growing and increasingly economically divided populations. I worshiped my father’s accomplishments— his buildings — as monuments to his creativity, without thinking about what they meant to those inside them or their larger role in the world’s ever-changing major cities. Honoring the stories of the displaced residents allows me to come to terms with the complexity of this moment and my personal and cultural history. My father was my refuge, his building was theirs, and in our shared loss, a connection has formed. For me in some inexplicable way, the building still exists through them and the real housing they continue to fight for. As Dito says, no one wants to live in an occupied building; people want intentional, dignified homes.

- Denise Zmekhol

In presence of the director Denise Zmekhol on March 23, 2024 at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montréal

Word of direction

In 2017, after two decades as an immigrant in California, I hear of a controversy in Brazil about Pele de Vidro: internationally renowned among architects, it has become occupied by some hundreds homeless people after being left empty for several years. The news reopens long-shut doors to a father I lost too early. Determined to somehow reconnect with him personally and as an artist, I return to Brazil seeking traces of him in the gleaming glass-walled office tower in the heart of São Paulo — the first of its kind in the city.

Looking up from the sidewalk, I encounter the building for the first time since my childhood. Four decades after my father’s death, I’m stunned to see it riddled with graffiti and filled with broken windows through which drying laundry and curtains billow while residents lean out to survey the city below. As the shocking state of the building begins to sink in, my curiosity grows and I set out to meet with those who have made my father’s masterpiece their home. Individuals functioning as informal landlords who charge the residents fees and claim to be maintaining the building turn me away. Frustrated but realizing how little I know, I meet Pericles, a passionate housing activist. He helps me understand São Paulo’s housing crisis and the goals of local activists, showing me some of the other 70 abandoned buildings now occupied by homeless people throughout downtown São Paulo. I discover that each occupied building is unique and organized differently. Pericles is unable to negotiate my entrance in Pele de Vidro, which makes him suspicious, since the people handling maintenance of other occupied buildings are activists and welcome me with open arms.

Being denied entry evokes the frustration and longing of my exile from my father’s life and work. Our estrangement began the year before he died, when he left our family. While repeatedly trying to negotiate my way inside the building over an extended period, I seek out people who complicate my childlike view of my father and his place in Brazil’s cultural history: architects and journalists who knew him and bring Brazil’s golden age, the early 1960s, alive. I learn from my father’s colleagues how architecture was stunted during the dictatorship that followed, and, more personally troubling, that my father did not actively resist the coup. Some of his friends did, and suffered the consequences of arrest, interrogation and exile.

These conversations raise questions of belonging and exclusion, the multiple meanings of shelter, displacement, access, and our own relationships to the buildings that surround us. I start to realize how different from my own worldview and political perspectives my father’s beliefs probably were. If he had lived, would we have drifted even further apart? Having grown up in a house he designed, how am I to think about this building of his that is now a home for others? I find myself drawn to these people who, like my younger self, call one of my father’s creations home.

After months of negotiations, the Pele de Vidro occupation leaders deny my request to film in the building. But I’m granted a glimpse inside in another way; a filmmaker who had documented the occupation’s early days sends me footage which allows me to vicariously experience the daily lives of residents inside the building. I reflect on my father’s experience as an immigrant, a Syrian refugee whose 280 project drawings played a significant role in Brazilian architecture, and his building’s latest residents, many of them immigrants from as near as Peru and as far as the Congo, who have not been welcomed by their new country as my father and I were.

Five months later, now back at my apartment in California, my cell phone buzzes insistently. It is May 1, 2018, and the Pele de Vidro is on fire. Phone calls and texts proliferate as I search for news. Footage on my cell phone captures the building engulfed in flames, and I watch its sudden collapse in an explosion of ash and debris. I am overwhelmed with emotions. How many have died? How can I accept that the building my father designed to celebrate the future has come to this tragic end in a city so dystopian that it would have been unimaginable to him? I get the next possible ticket to Brazil, asking myself during that long flight what might remain.

When I arrive, police cars, ambulances and the press are surrounding the street in front of the building. Orange firefighter helmets emerge from the smoke as rescuers search for survivors. Dust rises from the debris that was the Pele de Vidro. At least seven people are buried in the ruins, and several are missing. Hundreds have lost a home. I am devastated. The whole city is mourning the human tragedy and the destruction of a cultural landmark. For me, there is another, very personal layer of grief: I feel as though I have lost my father all over again.

Blindly, I turn the corner and discover people setting up tents, moving as if in slow motion – or in shock. The displaced residents are creating an encampment outside the building and now, without the occupation leaders there, I can freely approach them. I spend the next month getting to know dozens of individuals and families, including several I’d seen from their windows. They tell me they were never consulted about speaking with me and would have enjoyed showing me around the building. They add that the people who had kept me out fled the fire and locked the residents in. Police have issued arrest warrants for the coordinators, believing them responsible for the fire. I show the residents my footage from outside the building and they enjoy seeing themselves in their former home, intact again.

My relationship with them deepens over time as I start to not only see the building and Brazil itself from their perspective, but also consider how the world’s cities accommodate their growing and increasingly economically divided populations. I worshiped my father’s accomplishments— his buildings — as monuments to his creativity, without thinking about what they meant to those inside them or their larger role in the world’s ever-changing major cities. Honoring the stories of the displaced residents allows me to come to terms with the complexity of this moment and my personal and cultural history. My father was my refuge, his building was theirs, and in our shared loss, a connection has formed. For me in some inexplicable way, the building still exists through them and the real housing they continue to fight for. As Dito says, no one wants to live in an occupied building; people want intentional, dignified homes.

- Denise Zmekhol

Overview of some festivals:

Venice Architecture Film Festival, finalist, Italy (2023)

Barcelona International Architecture Film Festival, Best Feature Documentary, Spain (2023)

International Film and Architecture Festival Prague, Czech Republic (2023)

Architecture Film Festival, Audience Award 4th place, Netherlands (2023)

Mill Valley Film Festival, USA (2023) — Audience Favorite for the category ¡Viva el Cine!

Hawai’i International Film Festival, as part of the New American Perspectives program

Venice Architecture Film Festival, finalist, Italy (2023)

Barcelona International Architecture Film Festival, Best Feature Documentary, Spain (2023)

International Film and Architecture Festival Prague, Czech Republic (2023)

Architecture Film Festival, Audience Award 4th place, Netherlands (2023)

Mill Valley Film Festival, USA (2023) — Audience Favorite for the category ¡Viva el Cine!

Hawai’i International Film Festival, as part of the New American Perspectives program

| Director | Denise Zmekhol |

| Director of Photography | Leonardo Maestrelli, Heloisa Passos, Otavio Pupo |

| Production | Denise Zmekhol |

| Associate Producer | Leah Mahan, Richard O’Connell, Nathalie Seaver, Amir Soltani |

| Executive Production | Anne Corcos, Nancy Blachman, Elizabeth King, Sally Jo Fifer, Sandie Pedlow, Jamie Wolf, Jacob Solitrenick, Jamie Wolf |

Session

Production

Denise Zmekhol

Denise Zmekhol is an Arab-Brazilian award-winning director whose films have been recognized for their elegant visual style and deft storytelling. Her documentary CHILDREN OF THE AMAZON was supported by ITVS and broadcasted on PBS. She co-produced DIGITAL JOURNEY, an Emmy Award winning PBS series.

Biographical notes provided by the film production team

Biographical notes provided by the film production team

Selected Films :

The secret Fatwa (2016−2017)

Bridge to the future (2016)

Dogtown Redemption (2015−2016)

From the ground to the cloud : Transforming Champanzee conservation with High-Tech tools (2013)

Children of the Amazon (2001−2010)

The secret Fatwa (2016−2017)

Bridge to the future (2016)

Dogtown Redemption (2015−2016)

From the ground to the cloud : Transforming Champanzee conservation with High-Tech tools (2013)

Children of the Amazon (2001−2010)

You would like